Megan Kyak-Monteith: We Play the Same ᐊᔾᔨᖓᓂ ᐱᙳᐊᓲᖑᔪᒍ

For this small body of recent paintings, Halifax-based Inuk painter Megan Kyak-Monteith recalls scenes from her childhood, in particular moments shared with her younger brother, as a means of addressing her experience of being raised away from her traditional homelands and extended family in Nunavut.

The keystone work in the exhibition is a work entitled Letia, Her Hands. Just 5 x 7 inches, this diminutive work shows an elderly hand assembling a jigsaw puzzle. For Kyak-Monteith, jigsaw puzzles, a commonplace trope for problem solving and mystery, resonate on a deep level for practical and personal reasons. The subject of the painting is Kyak-Monteith’s great-grandmother. The two shared very little common language, Kyak-Monteith’s Inuktitut having been as limited as her great-grandmother’s English. In the absence of conversational exchanges, Kyak-Monteith’s primary means of getting to know her great-grandmother was through preparing food and doing jigsaw puzzles together. Her connection to her great-grandmother was through the physicality of those activities, and so she is able to recall their closeness through these actions of making.

The painting, a warm palette of rich tones and intimate scale, is dense with painterly brushstrokes, rendering Kyak-Monteith’s hand as present in the work as the subject itself. Making this painting of her great-grandmother assembling a picture—the puzzle—presents a poetic moment that further intertwines the two women in parallel acts of making; invoking, for the artist, the connection to her late great-grandmother. In an equally intimately scaled video work, Kyak-Monteith has animated a previous painting of her great-grandmother’s hands using an ulu to cut up maktaaq (whale).

In Self-portrait as a Grandmother, Kyak-Monteith portrays herself wearing clothing in styles that her grandmother would have worn or that were actually given to her by her grandmother. The act of wearing those clothes, the artist says, is a gesture toward feeling closer to or getting to know her grandmother. By painting herself in these garments, Kyak-Monteith enacts a visceral connection to her grandmother.

In connection with this image, the artist also mentions the traditional belief among her family and people that something of a person who passes away will live on in a younger family member when they are named after the person who has passed away. The artist’s younger brother, for instance, is named after a late renowned storyteller (the boy himself is now also a good storyteller). In a like manner, Kyak-Monteith’s grandmother calls the artist’s younger sister “Little Ataata”, meaning Little Father, as the child resembles her late grandfather. In her work, Kyak-Monteith similarly intertwines her sense of self with her sense of the family members who have either passed away or live in her home territory of Nunavut far away from her new base in Halifax.

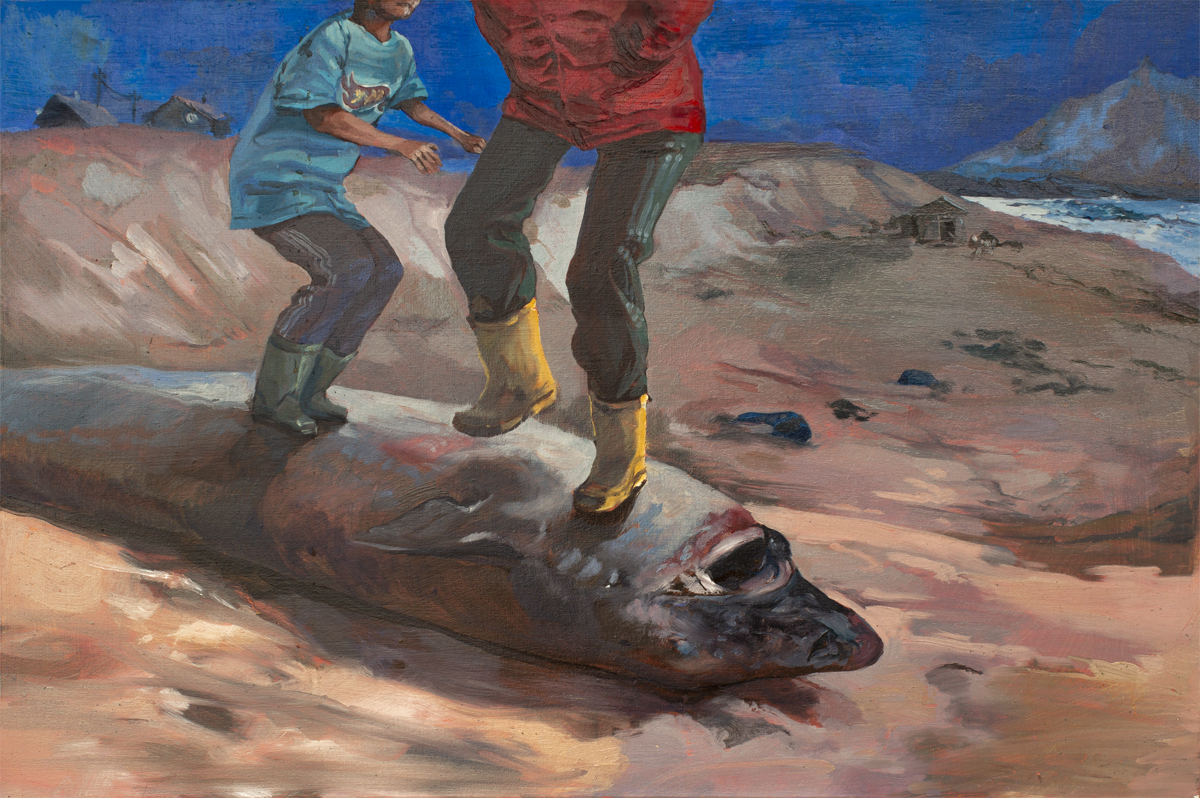

Further complicating the effect of intertwining identity within her family, Kyak-Monteith, who has moved away from her family home while her younger brother continues to live with their parents, somehow sees her brother as being a stand-in for her in that home. In this conception, the siblings are intertwined in their position in the family. In relation to the painting Shark Womp, Kyak-Monteith tells a story about encountering a dead shark and acknowledges being unable to distinguish between her own memory of the actual event and her recollection of her brother’s re-telling of the event years after it happened. In the artist’s imagination, then, the siblings’ memories—and their identities—intertwine.

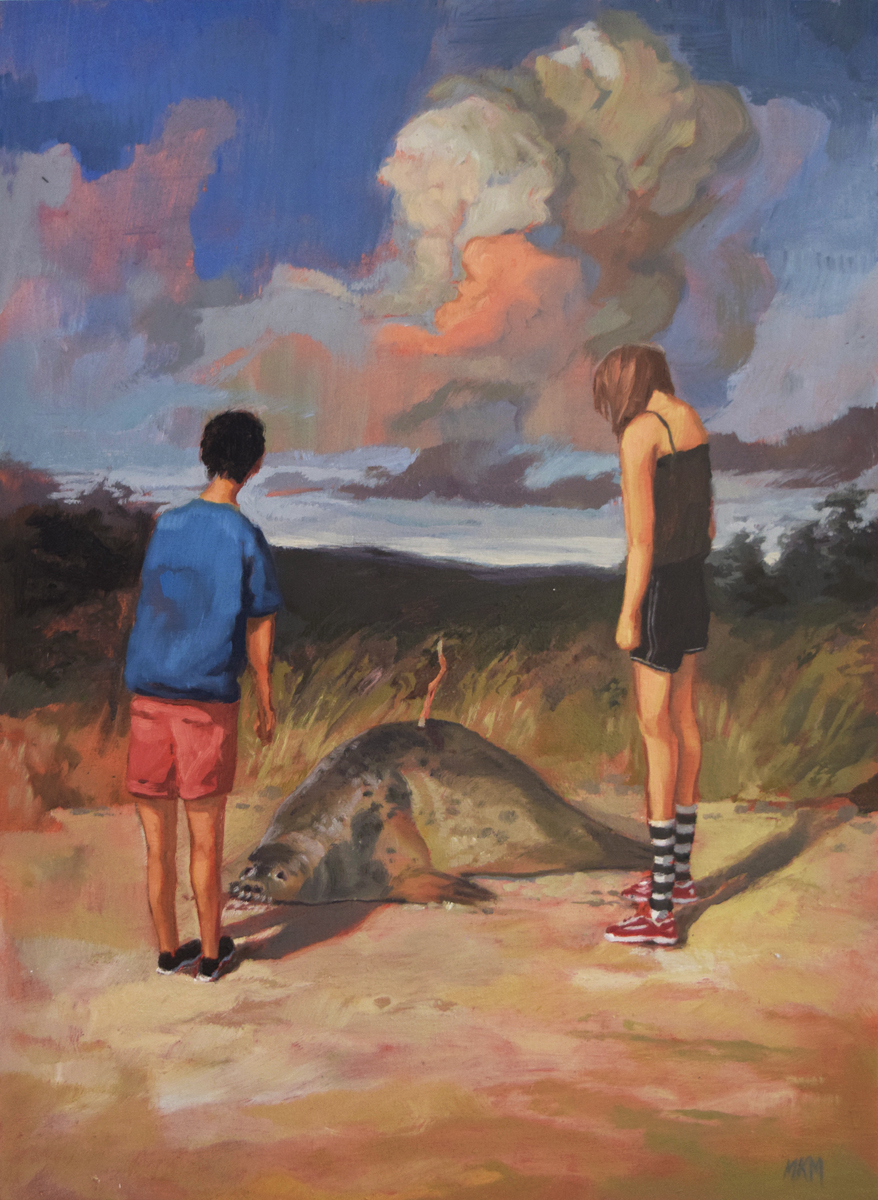

Even more poignant is the painting Seal on Road, a depiction of a shared memory from Kyak-Monteith and her younger brother, in which they found a dead seal that had been struck by a car on a rural dirt road in Nova Scotia. The seal’s displacement on a dirt road, far away from any ocean or river, speaks to the siblings’ shared experience of being displaced from their home territory north of the Arctic Circle. The image of the seal, an animal commonly hunted for food and fur in Nunavut, incongruously appearing of all places on a dirt road in Nova Scotia recalls the artist’s own feeling of being so far from her original environment.

Other works in the exhibition depict scenes from their childhood that blur the boundary between memories of actual events and interpretations of those events as they were being re-imagined at the time they were being experienced. In POV You Are The LEGO We Are Burying, we see the artist as a child, together with her brother and their friends, from the point of view of a miniature toy that is being buried. According to Kyak-Monteith, the children would occasionally bury such objects only to dig them up later, a performance that allowed them to pretend that they had found the toys. The depiction, then, is actually of the imagined experience of the toy figure at the centre of a story. The children in the scene are constructing a memory to replace that of the actual event. The subject/object and truth/fiction of the memory are flipped and blurred.

Collectively, this small collection of works speaks to a uniquely Inuk diasporic experience, and dances around the notion of self-identity being something fluid, constructed from a blending of actual lived experience and what is decisively imagined. The exhibition provides insight into Kyak-Monteith’s practice of embodying a lived experience of personal history and cultural heritage.

If many of the great, celebrated Inuk artists of recent decades have gained notoriety for their art showing modern Inuit life in traditional homelands, Megan Kyak-Monteith belongs to a new generation of contemporary Inuit artists who are taking up traditional and non-traditional forms of art to provide insight into the experience of living outside Inuit Nunangat (traditional homelands).