Written by Robin Laurence

Love and happiness radiate from Janet Nungnik’s extraordinary textile art, qualities, she has said, that originate in childhood memories of her close-knit family and life on the land. Her earliest recollections, celebrated in many of her acclaimed wall hangings, were formed at a far remove from the hamlet of Baker Lake (Qamani’tuaq), where she has lived and worked for many years. Nungnik was born Ariaut Anautalik in 1954, in a small camp west of Hudson Bay, in the Kivalliq region of what is now Nunavut. Through the marriage of her parents, Martha Tiktak Anautalik and William Anautalik, she is a member of the inland-dwelling Ihalmiut and Padlermiut peoples, distinctive cultural groups within what is known collectively as the Caribou Inuit.

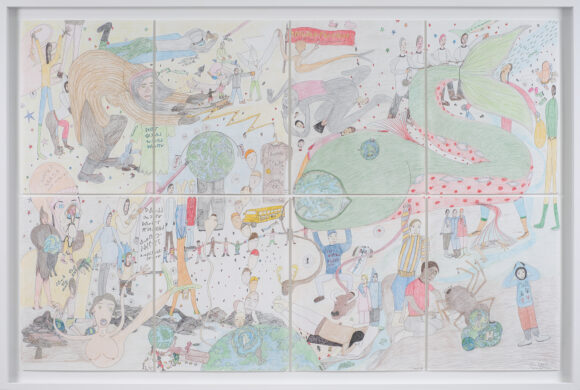

Her art is richly narrative and includes scenes of children playing, families sleeping cosily together inside iglus, dogsled races, community dances and loved ones returning from hunting and fishing expeditions. Rainbow of Memories, 2004, situates a parka-clad figure on a dogsled in a colourful landscape populated with ookpiks and butterflies and overarched by a rainbow, a symbol of gratitude for the rain. At the bottom of this wall hanging, a young girl swims in blue water, her caribou-skin clothes and boots carefully arranged on a Hudson’s Bay blanket on the shore. As with all Nungnik’s works, the forms are crisply cut and deftly appliquéd on wool duffel, then embroidered overall with such consistency that the stitches, which include the feather, herringbone and arrowhead stitch, function as delicate washes of colour over the solid-hued passages of cloth.

Nungnik may also employ beading in her wall hangings, to represent the decorative patterning on the clothing of her depicted figures. From the 19th century forward, Inuit women used trade beads to adorn traditional clothing such as parkas, and beads have subsequently found their way into Inuit wall hangings. The transition is neatly circular: before Jessie Oonark created the first Inuit wall hanging in 1964, inaugurating a new and desirable art form in the North, the women of Baker Lake and other settlements generated income by making beaded and embroidered clothing and accessories for sale to Canadians in the South, through government-run arts and crafts programs.

In Vancouver last spring for the opening of her solo exhibition at the Marion Scott Gallery, Nungnik sat for a videotaped interview in front of an untitled wall hanging. Made in 2004, it depicts a scene from her childhood in which she skips rope, her brother plays with a ball and string, her mother stands beside a trout-filled body of water and fish hang on a line to dry. “I was a very happy child,” she said. “I looked after my brother Eric, we played lots, we walked all over the tundra…. My father was always busy mending things. My mother was always busy drying fish…. As long as someone was watching over us, we always felt safe.” Her semi-nomadic family dwelt in such isolation that, for the first few years of her life, Nungnik thought they were the only people in existence. Occasionally, her father would leave their camp and take fox and wolf pelts to trade in some distant and mysterious place. When he came home, she said, he brought with him “strange and beautiful things.”

Read the full article, written by Robin Laurence, in Border Crossings